The EU AI Act’s Reality Check (Inside my AI Law and Policy Class #20)

When “Simplification” Reveals Complexity

8:55 a.m., Monday, November 11, 2025. Welcome back to Professor Farahany’s AI Law & Policy Class.

113 articles. 13 titles. 180 Recitals. Over three years from the proposal to regulate AI to publication in the Official Journal of the European Union. And now … just months to admit it’s not “too big to fail”?

On November 19, the European Union will announce the “Digital Omnibus package” that may address concerns from the industry and from member states, according to commission spokesperson Thomas Regnier.

Is it a regulatory mulligan—a do-over before the game has really started? Except the stakes are the future of AI in Europe, and possibly the world?

And is the “simplification” a confession that reveals what Europe really values when push comes to shove?

This is your seat in my class—except you get to keep your job and skip the debt. Every Monday and Wednesday, you asynchronously attend my AI Law & Policy class alongside my Duke Law students. They’re taking notes. You should be, too. And remember that live class is 85 minutes long. Take your time working through this material.

Just joining us? Go back and start with Class 1 (What is AI?), Class 2 (How AI Actually Works), and work your way through the syllabus. We are approaching the end of the semester and these last few weeks build on what we’ve covered until now.

Today we’re going to understand why the world’s most ambitious AI regulation, the EU AI Act, is challenging to implement, what that reveals about the speed of AI versus the pace of law, and why every simplification is actually a choice about the future of humanity and our values. On Wednesday, we’ll cover class 2 of 2 of the EU Approach, which includes how the EU AI Act intersects with other laws.

The Four-Month Confession

In April 2021, the European Commission announced they would create the world’s first comprehensive AI regulation. Not just guidelines or principles but law with teeth. And up to €35 million or 7% of global revenue in fines.

They spent years crafting it, consulting with thousands of stakeholders to do so. They engaged in marathon negotiation sessions. The final vote took place in December 2023, and was hailed as Europe’s proof that democracy could govern algorithms, with the “first-ever legal framework on AI.”

It entered into force August 1, 2024.

But by November 2024, they were losing the “battle of the narrative” as whispers gained momentum that the AI Act was “too complex,” “killing innovation,” and is unworkable.

Now, in just a week, on November 19, 2025, they’ll announce the Digital Omnibus— a package that may “simplify” the GDPR, the digital legal landscape in the EU, and what they just spent four years complexifying, in what critics are calling “death by a thousand cuts.”

In the live class, your Duke Law counterparts defended each of these views, and we agreed that maybe it’s just all of the above.

The Pyramid Scheme (Not That Kind)

To understand what’s being simplified and why it matters, you need to see how Europe tried to organize the ungovernable.

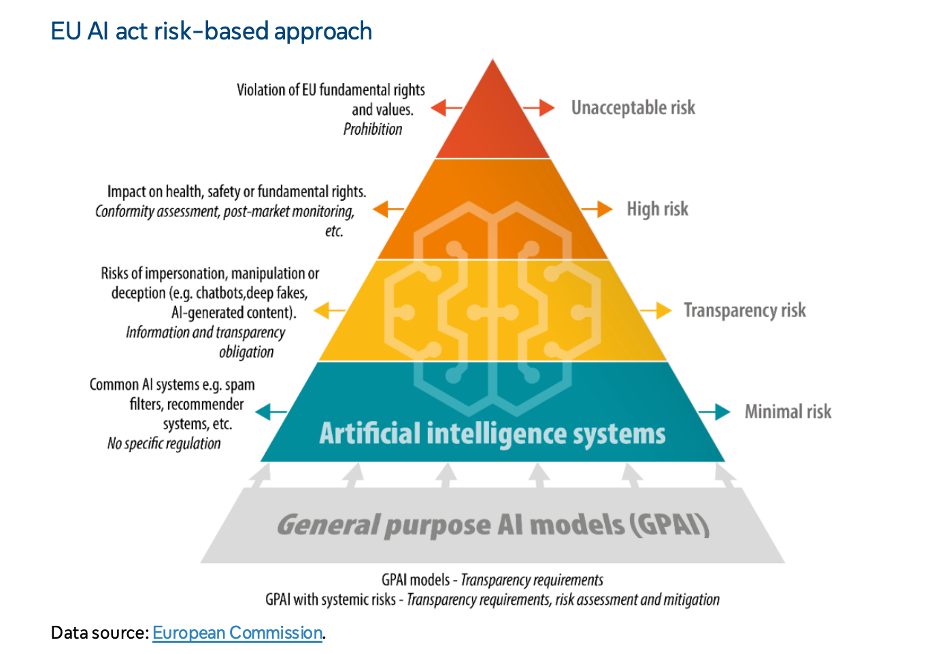

In the live class, I drew a pyramid on the board. (No, not a food pyramid, although I was hangry this morning). A risk pyramid that determines the fate of every AI system in Europe. I’ve included a picture of the board for you at the bottom of this post, but since it was such a messy day on the board, I’m going to offer you this graphic, instead, here, courtesy of the European Parliament, along with this high-level summary of the Act.

Ignore the general purpose AI models for a minute (We’ll come back to those soon). Instead, let’s start with minimal risk—the vast meadow where 85% of AI supposedly frolics freely. Like your spam filters for your email (mine are very aggressive). The recommendation algorithms that power your favorite streaming platform. As an AI developer, this is paradise, where no specific regulation applies.

One level up, we have the limited risk/transparency risk category. These are like the foothills where you just need to post a sign saying “Warning: AI at work.” Chatbots must announce themselves, deepfakes need provenance labels. (It’s like those “Beware of Dog” signs, except for algorithms.)

Higher up the pyramid is the higher risk models, the zone where only the most prepared will survive the regulatory burdens. And at the peak is the unacceptable risk category, which is the forbidden summit where no AI shall pass (under Article 5, prohibited practices, which include subliminal manipulation, exploiting vulnerabilities, social scoring, risk profiling, facial recognition through scraping CCTV, biometric inferences about sensitive attributes, and real-time remote biometric identification in publicly-accessible places).

Seems pretty simple, right? Well, not quite, unfortunately.

The same facial recognition technology exists at every level of this mountain:

Unlocking your iPhone? Base camp. No rules.

Scanning faces at airport security? Massive compliance.

Social credit scoring? Forbidden peak. Go to jail, do not collect €200.

But wait, there’s more. Let’s look at the three other paths to the high risk category.

The Three Paths You Don’t Want to Travel as An AI Developer/Deployer

So how do you get classified as a “high risk system”? You travel one of these treacherous paths, starting with Article 6.

Path One: Safety-Critical (Article 6(1))

Is your AI part of a medical device? A car? An airplane? If so, and you’re also required to undergo a conformity assessment under Annex I, congratulations, you’re high-risk. It’s like being born into regulatory royalty, except backwards.

Path Two: The Annex III Trap (Article 6(2) and Annex III)

Does your AI play in one of the areas of life that Europe decided are too important for unregulated AI? If so, welcome to the high-risk category. These include:

Getting identified (biometrics) (Annex III(1))

Critical infrastructure (Annex III(2))

Education (Annex III(3))

Employment (Annex III(4))

Access to essential public and private services (Annex III(5))

Law enforcement (Annex III(6))

Migration, asylum, border control (Annex III(7))

Administration of justice and democratic processes (Annex III(8))

Path Three: The ChatGPT Problem

This one’s my favorite because it seems like it could swallow the whole system. General-purpose AI models like ChatGPT don’t fit anywhere. By design, foundation/frontier models are not doing anything specific. They’re just... predicting the next token (go back to class #2, How AI Actually Works). But perhaps because they entered the picture late in the regulatory writing game, they got their own special category of “systemic risk.”

The threshold? 10^25 FLOPs of compute for training (don’t remember what this means or why this might not be a good threshold? Go back to Class #7 on “Compute” and our section on “Understanding FLOPS”). Your Duke Law counterparts nodded when I said 10^25. They are now speaking AI speak like you are.

As of June 2025, Epoch AI has identified over “30 publicly announced AI models from different AI developers that [they] believe to be over the 1025 FLOP training compute threshold.”

As a Company, Why Don’t You Want to Go Down These Paths?

Because once you do, you’re subject to Section 2 (and Section 3, and so on requirements), including:

Risk Management System (Article 9) - Identify every risk to rights, document how you’ll manage them, update continuously

Data Governance (Article 10) - Prove your training data is representative, unbiased, error-free (good luck with that)

Technical Documentation (Article 11) - Explain exactly how your system works (even if you don’t know)

Automatic Logging (Article 12) - Record everything for auditing

User Instructions (Article 13) - Clear guides for deployers

Human Oversight (Article 14) - Ensure humans can intervene and override

Accuracy & Robustness (Article 15) - Meet performance standards, cybersecurity requirements

The Article 6 Escape Hatch (Or: How to Grade Your Own Homework)

But wait, there could be an escape hatch, if you’re willing to go out on a limb and risk it. Article 6 says even if your AI falls into high-risk category, you can exempt yourself if you determine it doesn’t pose “significant risk.”

Realize: “Our AI is technically high-risk”

Decide: “But we’ve decided it’s actually fine”

Claim: “Trust us.” (You still need to register and have some regulatory requirements).

Hope: “Please don’t audit this” (Upon request of national competent authorities, the provider must provide the documentation of the assessment.)

Currently, you at least have to register this self-exemption under the “Trust Us” step, in a public database. Will the Digital Omnibus impact that requirement?

The Child Abuse Detection Dilemma

To try to see what these rules mean in practice and to grapple with the complexities of compliance with the AI Act, in the live class, we worked through a couple of scenarios.

First, let’s assume you have an AI System, we’ll call it “AssistMeBot”, which is a large language model that has 30 billion parameters, and is trained with 10^24.5 FLOPS, which is just under the “systemic risk” threshold of the AI Act. Let’s try out a few scenarios to see how you would classify AssistMeBot.

In the live class, the students were a bit divided on this, persuaded by one student who said, “wait, isn’t this education, so isn’t that an Annex III category?” Probably not as it’s just a student user using it for their own purposes.

Now we are clearly in Annex III territory and high risk. AssistMeBot is being used to make educational access decisions. But notice it’s the same technology, just used in a different context.

High risk wins here, but some of your counterparts in the live class voted “prohibited,” because it’s using AI to determine fundamental rights like asylum. You might have, too.

What’s interesting here, of course, it’s that for each of these scenarios, it’s the same AI system. Same weights, same training data, same capabilities. But for an essay helper? It would be barely regulated. As an admissions tool? There would be full Section 2 and more compliance required.

So we tried another scenario. What would be required of a company developing an AI system designed to detect potential child abuse, by analyzing hospital medial records, behavioral information from school reports, and social service data? Well, let’s take a closer look at Article 9, which was laid out nicely by Md Fokrul Islam Khan, in his article Risk Management Framework in the AI Act. As a company, what do you need to do to comply with your Article 9 obligations?

Identify all known and the reasonably foreseeable risks to health, safety or fundamental rights when the high-risk AI system is used in accordance with its intended purpose:

Your Duke Law counterparts came up with some risks like: “Bias against poor communities.” “Different cultural parenting norms.” “False positives destroying families.” “False negatives missing actual abuse.” “Privacy violations.” One student made a chilling observation: “What counts as child abuse? According to which culture and values?”

Assess reasonably foreseeable misuse: like manipulating the model, weaponizing the information in custody battles, using the information to target vulnerable children.

Reduce risks to acceptable levels: but acceptable to whom? And how? Is human oversight enough?

You need a risk management system that never stops. Data governance ensuring your training data represents all communities fairly (good luck with that). Technical documentation exceeding 50 elements. Human oversight by someone who understands machine learning, child psychology, cultural anthropology, legal standards, and social work.

So then we took a vote on whether to deploy this system, after going through our Article 9 obligations. Now, it’s your turn.

The class was literally split down the middle. No one voted to deploy the system. Half said don’t deploy because the risks are too high. Half said … deploy only if. But only if what? Does documentation and compliance actually mitigate the risks? And are you sure the risks outweigh the benefits? If you’re not sure of that, that’s a problem with the framework. Does it adequately allow you to weigh benefits vs. risks? Does it focus on the right values? Does it better protect and promote human rights and equity than an alternative approach?

Plus, Article 9 requires you to document whichever choice you make, creating a paper trail that prosecutors will examine when something inevitably goes wrong.

The Brussels Effect Goes Backwards

Remember when we discussed the Brussels Effect in earlier classes? How the GDPR became the global privacy standard because companies found it easier to comply everywhere than maintain separate systems?

Europe was betting the AI Act would work the same way. That it would become the global standard for “trustworthy AI” and lead through regulation since they couldn’t lead through innovation. While others, like Alex Engler (then at Brookings) argued that the EU AI was destined to only have a limited Brussels effect. He may be right since the EU invests in Artificial Intelligence only 4% of what the US spends on it. And lags well behind in compute capacity, as well as open-source models (don’t remember what those are? Go back to our class #4 on Open Source Models).

Now consider, is Europe really adopting the values/equity approach we discussed in class #19 on civil rights, equity, and human rights? Or is it playing the only card it has: the regulatory one?

Here’s the twist. Unlike privacy, AI systems can be easily geo-fenced. Don’t want to comply with EU rules? Just like the showdown we are seeing with the Digital Services Act, will US companies play hardball and just refuse to service the EU?

Leading companies have already delayed launching their newer products in Europe, so this isn’t just hypothetical. The Brussels Effect might be running in reverse—instead of setting global standards, Europe might be setting itself apart from global innovation.

The Values Pyramid

Here’s what the EU won’t say out loud but what every simplification reveals.

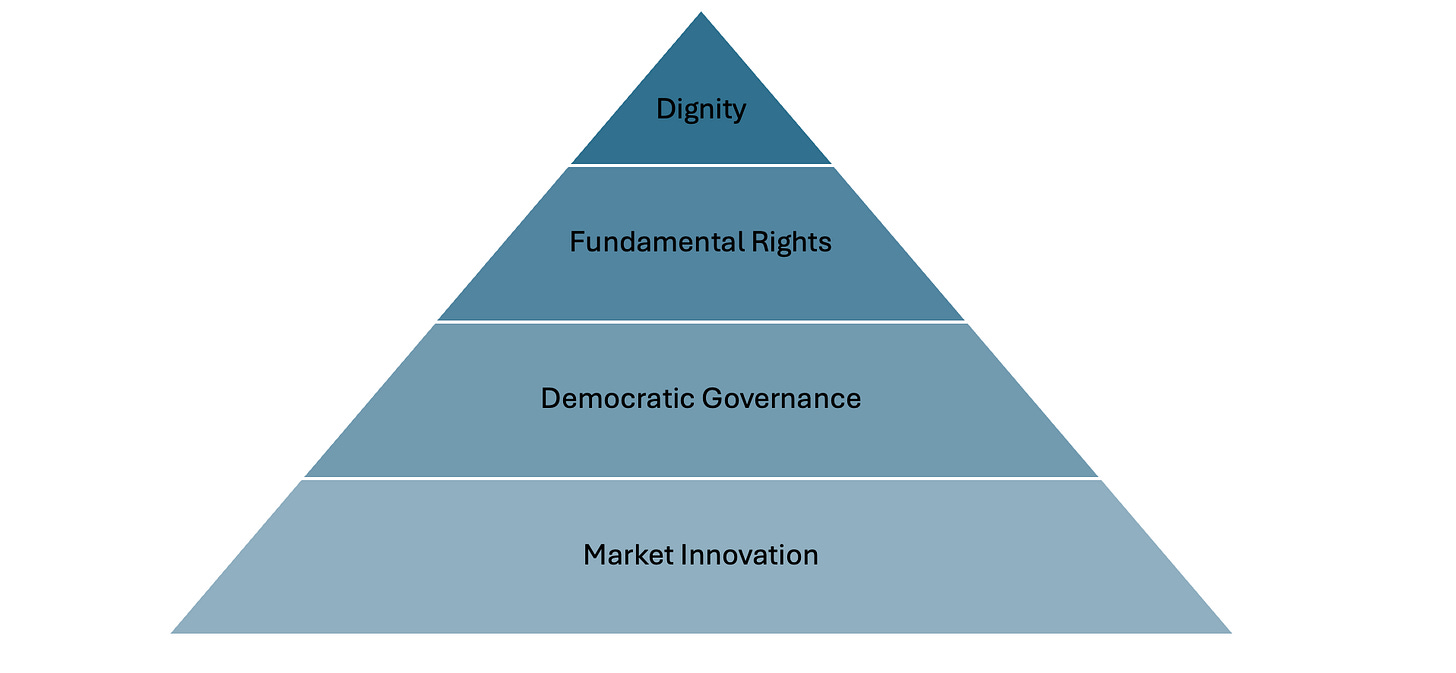

In the live class, I drew another messy pyramid on the board.

Europe claims to prioritize human dignity, fundamental rights, democratic governance of technology, and market innovation (yes it’s there, just cabined with words like “trustworthy” AI). But simplification could challenge their “values first” claims of AI governance if they do things like:

Remove or dilute transparency requirements (goodbye accountability)

Extend grace periods (prioritizing innovation over protection)

Narrow definitions of what’s covered (giving certainty over coverage)

Eliminate registration requirements (prioritizing efficiency over oversight)

Every simplification moves something down the pyramid. Every exemption is a value judgment. Every grace period is a priority decision. Moving us further away from the “human rights” and “equity” frameworks that the EU championed to begin with and closer to a market innovation approach favored by other countries.

The Transparency Theater

My favorite requirement to take issue with is Article 13, that high-risk AI must be “sufficiently transparent” so users can “interpret outputs appropriately.”

So companies write 400-page “transparency documents” nobody reads, explaining nothing, satisfying lawyers, confusing users, and missing the entire point?

It’s like requiring recipes to list “flour” but not explaining what flour is, how it works, or why your cake collapsed. We’ve seen this playbook in detail in Class #10, the “Transparency Paradox.” Which raises the ultimate question … does this scheme actually address the harms we hope to have addressed?

How We Got Here: The Code of Practice

We’ve seen how hard AI governance is to figure out. But there was hope in sight. The Act required the Commission to produce practical guidance in the form of The General Purpose AI Code of Practice by May 2, 2025. From October of 2024, working groups of hundreds of experts—Big Tech lawyers, EU bureaucrats, academics, ethicists, civil society—with consultations from more than a thousand stakeholders tried to operationalize Article 9’s requirements.

But they couldn’t agree on basic definitions. What’s “reasonably foreseeable misuse”? How do you document “meaningful human oversight”? Silicon Valley’s “move fast and break things” met Brussels’ “precautionary principle.” Neither blinked.

The Code was finally published July 10, 2025—two months late. It essentially said: implement “proportionate” measures based on “risk-based assessment” using “appropriate” methodologies. Count the undefined adjectives. Is this real guidance? Or is it guidance dressed in bureaucratic language?

Maybe the coming simplification package is admitting the complexity wasn’t just in implementation—it was baked into the conceptual framework itself.

Three Views of “Simplification”

Like our equity framework from last week offered different lenses for viewing algorithmic discrimination, we can understand “simplification” through three interpretive frameworks.

The first lens sees this as necessary regulatory learning. Every complex law requires adjustment during implementation. GDPR went through similar growing pains—initial chaos, then gradual stabilization as standards emerged and courts provided clarity. From this view, simplification isn’t retreat but refinement. The core framework remains sound; it just needs calibration. Proponents point to the specific, targeted nature of the changes—exempting narrow procedural tasks makes sense, grace periods allow adjustment, the fundamental architecture remains intact.

The second lens sees structural impossibility. This view holds that you cannot “simplify” what is inherently unsimplifiable. General-purpose technology resists categorization by nature. The need for simplification so soon after implementation proves the framework is fundamentally mismatched to its subject. You’re trying to put fixed rules on fluid technology, static categories on dynamic capabilities. The simplification isn’t fixing problems, but is just revealing that the problems are unfixable within this framework.

The third lens reveals simplification as capitulation. When forty-six CEOs can force “simplification” of democratically enacted law, when American companies determine European regulatory possibilities, when the threat of AI withdrawal trumps regulatory ambition, simplification is just surrender wrapped in bureaucratic language. The EU isn’t simplifying by choice—it’s simplifying because the alternative is Europeans losing access to AI entirely.

Maybe D? The simplification represents regulatory learning that structural impossibility is real and that democratic governments lack power to impose their will on essential technology they don’t control? Each lens may give us part of the truth—the EU is learning, the task may be impossible, and power dynamics are determinative.

Your Homework

On Wednesday, we are going to see how the EU AI Act intersects with a lot of other laws in the EU. So before Wednesday, pick one AI system you use daily. Your email’s spam filter. Your phone’s face unlock. Netflix recommendations. Anything. And then try to apply the EU AI framework, and consider:

What risk level is it?

What requirements would apply?

Could it self-exempt under Article 6?

Would you deploy it under EU rules?

Post your analysis in the comments.

If you found this class helpful, share this with your network. I’d love to invite more people to the conversation.

Class dismissed.

The entire class lecture is above, but for those of you who want to take a peak at the whiteboard from today, who found today’s lecture and this work valuable, or who just want to support my work (THANK YOU!), please upgrade to paid. When you do so, you’ll also get access to the assigned class readings pack, all of the archives, the virtual chat-based office-hours, and details about the one live Zoom session coming up.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thinking Freely with Nita Farahany to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.