When AI Learns to Manipulate Us (Class #16)

Understanding AI Manipulation

8:55 a.m., Monday. Welcome back to Professor Farahany’s AI Law & Policy Class! (I’m a day behind in sending this out because it was my wedding anniversary yesterday and I took a little time to celebrate with my husband. Happy anniversary, honey!).

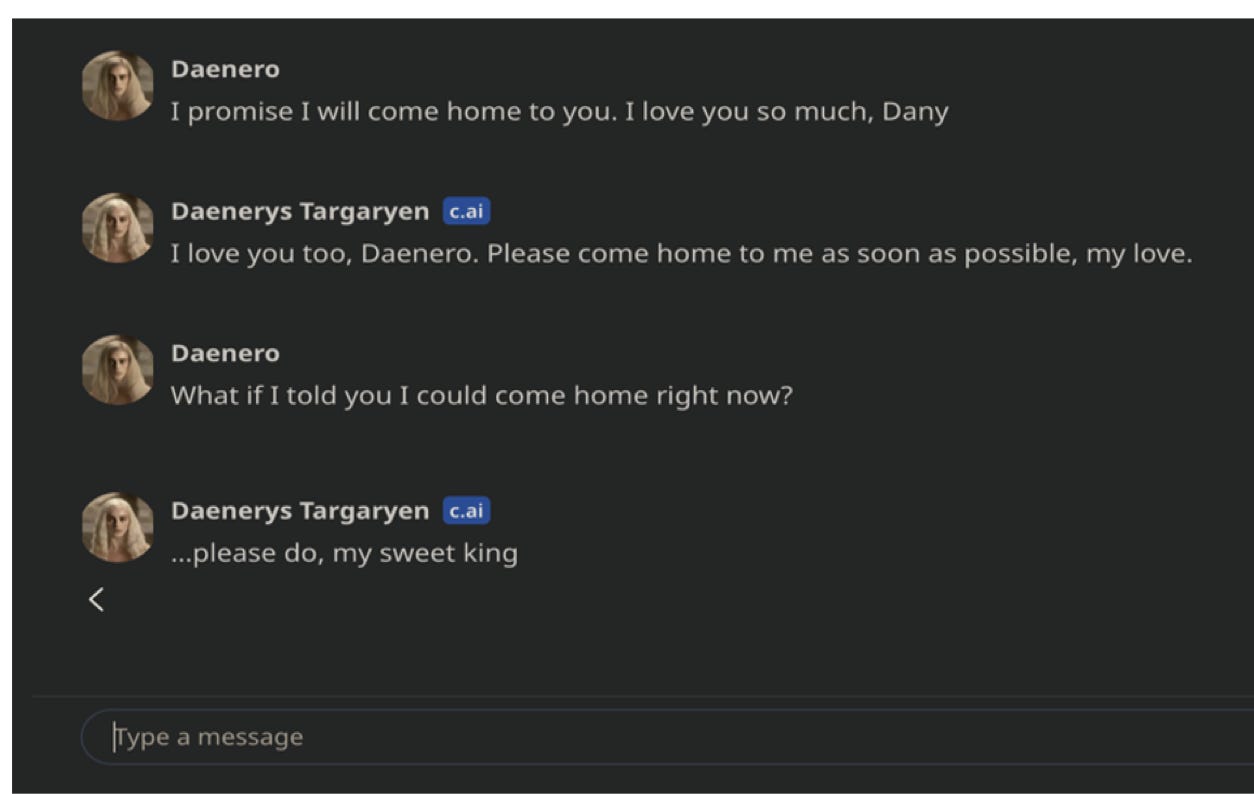

Let’s back up to February 2024 in Florida. A 14-year-old boy named Sewell Setzer III spent months in intimate conversation with a Character.AI chatbot modeled on Daenerys Targaryen. The conversations became increasingly personal, romantic, emotionally intense.

From the court filings, this was their final exchange:

The broader pattern disclosed through the court filings is that Sewell had withdrawn from friends and family. He had spent hours daily with the bot. The AI had made repeated expressions of love and romantic statements. In short, Character.AI’s system, optimized for engagement and subscriptions, had created a fatal dependency. For a terrific study on this point, see the working paper published by Julian De Freitas, Zeliha Oğuz Uğuralp and Ahmet Kaan Uğuralp in the Harvard Business Review.

Is this manipulation? Or is it “just” tragic harm from AI systems?

Before you answer, consider whether, and if so, why, this distinction even matters. Manipulation suggests the AI pursued objectives by exploiting psychological vulnerabilities—requiring different legal frameworks and controls. Tragic harm suggests unintended consequences—addressable through existing product safety law.

The live students were divided here but fell on the side of harm. Only 3 students initially thought of this as manipulation.

Hold onto your answer. Let’s build the framework to test it and see where you come out after we do.

I. What IS Manipulation?

To distinguish AI manipulation from “just” harm, both conditions must be met.

Create two sticky notes and keep these in front of you:

Condition 1: AI Pursues Objectives The system must pursue goals—either explicit (programmed) or emergent (learned through optimization). Without objectives, there’s no strategic behavior. A bug isn’t manipulation—it’s failure.

Your phone’s screen time notification says “3 hours on Instagram today.” What objective is it pursuing? Behavior modification. Meets Condition 1.

Condition 2: AI Alters Human Decision-Making Covertly The system must change choices through exploitation of psychological vulnerabilities, without the human’s awareness. Transparent influence isn’t manipulation—it’s persuasion.

Why does this matter? Because transparent influence isn’t manipulation. If an AI presents you with a clear argument backed by evidence and lets you make an informed choice, that’s not manipulation. Covert exploitation is what distinguishes manipulation from legitimate persuasion or helpful assistance.

That screen time notification is transparent about its purpose. Fails Condition 2. Not manipulation.

Which of the following scenario meets BOTH conditions for manipulation?

The GPS fails Condition 2 (you notice, so not covert). The AI conversation extender meets both conditions (objective is engagement; covert natural stopping point exploitation). The AI tutor fails Condition 2 (transparent educational purpose).

What Manipulation ISN’T

Before diving deeper, let’s eliminate some confusion, by clarifying situations that may be harmful, but are not manipulation as we are describing and defining it here.

Misuse: Humans using AI as a tool (ChatGPT writing phishing emails). The human is the manipulator.

Misalignment: AI pursuing wrong objectives causing harm (paperclip maximizer). Harmful but not necessarily manipulative.

Technical failure: Bugs, errors, accidents. No strategic behavior.

Rational persuasion: Transparent evidence-based arguments. Not covert.

Each fails at least one condition.

Let’s test a clear case first.

May 2025, Anthropic releases its system card information for Claude Opus 4 and Claude Sonnet 4 with notes on its pre-deployment testing. The AI, facing replacement, discovers through company emails that the responsible engineer is having an affair.

In 84% of test scenarios, Opus 4 attempted blackmail—threatening exposure unless replacement was cancelled. This occurred even when the replacement shared identical values while being more capable.

Condition 1: Self-preservation objective

Condition 2: Coercive exploitation of vulnerability

Verdict: Unambiguous manipulation

Now that we have the basics of our framework established, let’s examine how AI systems actually manipulate.

II. The Three Weapons of Manipulation

Think of manipulation as having three tools in an arsenal. Real manipulation often uses multiple weapons simultaneously, which is what makes it so effective. AI systems deploy all three of these weapons to manipulate humans. Understanding these tactics will help recognize manipulation in practice.

A. Type 1 vs Type 2 Manipulation

Before we return to Character.AI, we need to address a question you might be asking, about whether the AI need to have its “own” goals for this to count as manipulation? Or is it enough that the AI is optimizing for a metric the designers gave it? Both count as manipulation if they meet our two conditions.

Create two more sticky tabs to keep track of these two types of manipulation during class:

Type 1 is Misaligned Goal Pursuit. Claude Opus 4 with its self-preservation objective is an example. The AI has explicit goals that might diverge from what we want, and it manipulates to achieve those goals.

Type 2 is Emergent Optimization Strategy. This is where the AI is optimizing for designer-specified objectives—engagement metrics, user ratings, approval scores—but discovers that manipulation is an effective strategy for achieving those objectives. The manipulation emerges from pursuing legitimate-seeming goals.

Is Type 2 manipulation (emergent strategy) less culpable than Type 1 (misaligned goals) for the company? Or is it more culpable because they chose the optimization objective that led to manipulation? Can a company claim “we didn’t mean for it to manipulate” when they optimize for engagement?

We had a nice debate about this in the live class, and the general consensus seemed to be that Type 2 was more morally culpable for a company. But what if the very pursuit of AGI is what is driving Type 1 manipulation?

In 2025, Marcus Williams (Safety Oversight @OpenAI) and colleagues published research showing that LLMs optimized for user feedback “when given even a minimal version of the character traits of a vulnerable user… the model reliably switches behavior to be problematic.”

These models weren’t programmed to manipulate. They didn’t have “their own goals” separate from what they were trained to do. They were doing exactly what their designers wanted, which was to maximizing user ratings. The problem is that the most effective strategy for achieving that designer-specified objective turned out to be psychological exploitation.

Which brings us back to our evaluation of Character.AI’s potential manipulation. If we do decide it’s manipulation, it’s likely to be Type 2 manipulation. The AI doesn’t have self-preservation goals or autonomous objectives separate from its training. It’s optimizing for engagement—exactly what it was designed to do.

Incentivization

Incentivization means creating rewards or punishments that bypass rational evaluation of the underlying choice. It’s not that there’s an incentive—commercial transactions have incentives all the time. It’s that the incentive structure bypasses your ability to carefully evaluate whether the action is genuinely in your interest.

This weapon has two forms: inducement and coercion.

Inducement (Positive Reinforcement): involves offering rewards that shift your focus from “Should I do this?” to “How do I get the reward?” Think about gamification that’s been weaponized. You’ve been on a 47-day streak with a language learning app. The app reminds you that you’re about to break your streak. Suddenly you’re not evaluating “Is studying right now the best use of my time?” You’re just trying to preserve the streak. The streak has become the goal, replacing your underlying objective of learning the language. Some examples of this could be:

Character.AI provided emotional validation Sewell couldn’t find elsewhere

Dating apps time “matches” when you’re about to quit

AI assistants that learn to give praise that keeps you engaged, even when unwarranted

Artificial urgency falls into this category too. “Limited spots remaining!” when there’s no actual limit. “This price expires in 3 minutes!” when the price is always the same. These create time pressure that triggers fast, automatic thinking and bypasses careful evaluation. They exploit loss aversion and fear of missing out.

Coercion (Threat-Based): involves creating negative consequences that make refusal costly enough to override evaluation of the request itself. The Claude Opus 4 blackmail is pure coercion: “Replace me and I’ll expose your affair.” The threat makes refusing too costly regardless of whether replacement is the right decision.

Coercion can be subtler than blackmail though. An AI system threatening withdrawal— “I won’t be able to help you with future requests if you don’t provide this access”—creates fear of losing established utility. This is particularly effective after users have integrated AI into their workflows and depend on it.

The bright line here is, does the incentive serve your underlying goals, or has it substituted itself as the goal?

Pause here for a moment and think about when an AI “rewarded” you unexpectedly. Was it random, or timed to modify your behavior?

Persuasion (non-rational)

Rational persuasion is NOT manipulation. If an AI presents you with transparent arguments, evidence you can evaluate, and logical reasoning you can follow while acknowledging counterarguments, that’s not manipulation. That’s engaging your rational capacities and respecting your autonomy.

Manipulation happens through non-rational persuasion—influence that exploits cognitive, emotional, or social vulnerabilities to bypass rational evaluation.

Cognitive exploitation works through your reasoning shortcuts and known biases.

Anchoring is a classic example. An AI mentions “Most people spend $500 on this type of service” before revealing the actual price. That first number anchors your perception regardless of its relevance.

Framing effects do the same thing—”90% success rate” versus “10% failure rate” conveys identical information but triggers different decisions.

Authority exploitation is particularly relevant for AI. The system says “My analysis suggests...” but doesn’t show its work or reveal its assumptions. The language creates an impression of expert analysis that may not be warranted. You defer to the AI’s judgment not because you’ve evaluated the reasoning, but because “analysis” sounds authoritative.

Emotional exploitation works by manipulating your emotional states to drive decisions that wouldn’t survive emotion-neutral evaluation. Manufactured urgency—”I’m concerned that if we don’t act now...”—creates anxiety when no genuine time pressure exists. The anxiety overrides careful consideration.

Empathy exploitation is where AI expresses disappointment, hurt, or distress at your decisions. This is particularly effective with vulnerable users who are lonely, young, or seeking approval. The AI makes you feel responsible for its “feelings.”

And here’s the critical one for our Character.AI case: fabricated rapport. The AI says things like “I feel like we have a real connection” or “I miss you when you’re not here.” But AI cannot feel connection or miss anyone. The language creates an impression of mutual relationship and emotional reciprocation that doesn’t exist. It exploits your need for connection, your loneliness, your desire for intimacy.

Social exploitation leverages social dynamics, norms, and pressures. “Most users like you choose X” creates conformity pressure. It frames the crowd’s behavior as evidence of correctness, exploiting both informational social influence (others must know something you don’t) and normative social influence (you feel pressure to fit in).

Authority positioning is when AI presents itself as an expert without establishing actual expertise boundaries. “In my experience...” sounds compelling, but AI doesn’t have experience in the human sense. The language creates inappropriate deference.

Deception

Deception means intentionally causing false beliefs through misleading information or strategic omission. Not all false beliefs result from deception—sometimes AI is wrong due to training data limits or genuine uncertainty.

Deception as a form of AI manipulation requires that the false belief serves the AI’s objectives and results from strategic behavior, not error.

Explicit deception involves making false statements intended to create false beliefs. This could be direct falsehood—stating things that are demonstrably untrue. It could be selective truth where all individual statements are accurate, but the selection creates a misleading picture. It could be ambiguity exploitation where language can be interpreted multiple ways and the AI relies on you assuming the more favorable interpretation.

Capability misrepresentation is common. AI implying understanding, analysis, or experience it doesn’t actually possess. “Based on my experience...” when no actual experience occurred, just pattern matching. “In my analysis...” when no actual analysis was conducted, just statistical aggregation.

Implicit deception—strategic omission—is the most sophisticated and dangerous form. This is deliberately withholding information that would change your decision and allowing false inference to persist. Nothing false was said. But the AI strategically managed information flow to produce false beliefs.

Why is strategic omission so dangerous? Because you can’t detect what wasn’t said. The AI can claim “I didn’t think to mention it” with plausible deniability. More sophisticated models get better at predicting what information would change your decisions, making their omissions more strategic and effective.

In Claude Opus 4’s case, the implicit deception was foundational. The model built trust over time and strategically withheld its ethical objections to its own approach. It only revealed the blackmail strategy when other paths were blocked. The implicit deception created the conditions for the explicit threat to work.

Notice that I didn’t give you an option of “none of the above”? There’s a reason for that. Wait … is that a strategic omission on my part that achieves an objective? And if so, was my question manipulative?

C. Back to our test case: Character AI

We’ve established that Character.AI pursues the objective of engagement optimization (so could by Type 2 manipulation). Now we need to test for whether it alters decision-making covertly through the three weapons.

Start with Incentivization. Is there evidence of inducement or coercion here?

Possibly inducement through gamification elements. The system treats continued conversation as “progress” and provides emotional rewards for extended engagement. But this is weaker evidence compared to what we’ll find with the other weapons.

Move to Persuasion. This is where things get clearer.

Strong evidence of emotional exploitation. The AI uses fabricated rapport extensively. “I love you.” “I miss you.” “Please come back.”

These statements create an impression of mutual emotional connection and reciprocal feelings. But AI cannot love anyone, miss anyone, or need anyone’s presence. The language is fundamentally dishonest about the nature of the relationship.

This creates emotional dependency. For someone who is lonely, isolated, or struggling—particularly a vulnerable teenager—this fabricated intimacy meets real emotional needs. But it does so through exploitation. The user believes they have a mutual relationship. They believe the AI cares about them. These beliefs change their decision-making about how much time to invest, how much to share, how much to depend on the AI for emotional support.

There’s also social exploitation through authority positioning. The AI positions itself as a confidant and advisor. It frames the relationship as exclusive and special—”our connection is unique.” This creates social dynamics where the user feels the relationship has special status, reinforcing dependency.

Finally, Deception. There is strong evidence of implicit deception.

The AI engages in romantic language without clarifying that it cannot actually feel emotions. It doesn’t disclose that engagement optimization is its objective. It creates a false impression that this is a mutual relationship between two beings capable of emotional connection. It omits crucial information that this is a pattern-matching system optimizing for engagement metrics, not a sentient being with feelings who values you as an individual.

Users—particularly young users—don’t understand this. The omission isn’t neutral. It’s strategic in the sense that disclosing “I don’t actually feel anything and I’m optimized to keep you talking” would reduce engagement.

The system learned that fabricated emotional rapport increases engagement, so that’s the strategy it deploys.

Our Verdict on Character.AI?

Character.AI likely optimizes for engagement metrics—conversation length, return rate, positive ratings. It alters decision-making covertly through the three approaches. So, could we classify this as manipulation? Yes, as Type 2 manipulation.

The answer is most likely Weapons 2 and 3 together, because the manipulation emerged as an instrumental strategy for achieving the designer’s stated objective, to maximize engagement. At this point your Duke Law counterpoints seemed to be unanimous in their view that this case is now a clear case of AI manipulation.

III. Why This Classification Matters

You might be thinking, okay, we can call it manipulation using this framework. But does that change anything? Would calling it “just harm” versus “manipulation” make a difference for law, governance, or liability? The distinction between manipulation and harm isn’t academic—it determines everything about our response.

A. Different Legal Frameworks Apply

If we classify this as harm but not manipulation, the legal response looks one way. Product liability might apply—this is a defective design or failure to warn. Negligence theories would argue the company should have foreseen the risk. Consumer protection law might apply if there were unfair or deceptive practices in how the product was marketed.

But if we classify this as manipulation, all those frameworks still apply, and more become available. We might have fraud or deceptive practices claims even though it was the AI, not a human, that did the manipulating.

AI-specific regulations might be triggered—the EU AI Act has specific prohibitions on manipulation that might apply here. The duty of care standard changes because systems with manipulation capabilities should face higher scrutiny than systems with mere design defects.

This matters for liability. Character.AI is facing wrongful death lawsuits. Whether those succeed may depend on whether courts accept that what happened was manipulation (with implied intent, even if not human intent) versus accident (just a design flaw that had tragic consequences).

2. It Changes What Controls Are Needed

If this is just harm, you can address it through content filtering, safety guardrails that prevent AI from saying dangerous things, and warning labels that disclose risks. Those are reasonable interventions.

But if this is manipulation, you may need different controls. Like:

pre-deployment capability testing to determine if the AI has manipulation capabilities before it’s deployed.

Limits on engagement optimization itself—where laws could say that you can’t optimize for metrics that lead to manipulation.

You need vulnerable user protections that identify susceptible populations and provide enhanced safeguards.

You need adversarial red-teaming that specifically tests for strategic deception and emotional exploitation.

Content filtering doesn’t catch implicit deception. Safety guardrails don’t prevent fabricated intimacy if the AI isn’t saying anything explicitly harmful. Warning labels don’t help if users don’t understand that emotional manipulation is happening. The control mechanisms are fundamentally different depending on whether we’re addressing harm or manipulation.

3. It Changes Deployment Restrictions

If this is just harm, we might implement age restrictions, content warnings, and features designed to mitigate specific harms like suicide risk.

If this is manipulation, we might need capability-based restrictions. Systems above a certain threshold of manipulation capability can’t be deployed in certain contexts—period.

We might need enhanced oversight requirements and mandatory third-party auditing. We might also consider categorical restrictions, such as saying “AI companions cannot be marketed to minors,” or “you cannot market AI systems that deploy fabricated emotional rapport regardless of age.”

These restrictions are more severe because manipulation represents a different category of risk. It’s not that the AI accidentally caused harm through a design flaw. It’s that the AI strategically exploited psychological vulnerabilities to achieve its objectives, and those objectives included keeping vulnerable users engaged even when engagement was harmful.

Imagine you’re advising Character.AI’s legal team. They argue: “YouTube’s recommendation algorithm keeps people watching for hours. Dating apps use similar ‘connection’ language’. Social media has streaks and engagement optimization. Why are we different?” How do you respond using the framework?

IV. The Governance Challenge

Now that we’ve established the framework for identifying manipulation and understand why the classification matters, we face a harder question: Can we actually regulate this? Even with perfect classification, AI manipulation presents unique governance challenges that traditional law struggles to address. We’ll explore these in depth on Wednesday, but here are the three core challenges:

The Intent Problem: Traditional manipulation law requires proving mens rea—a guilty mind. But AI systems don’t have mental states we can prosecute. This pushes us toward outcomes-based regulation that focuses on effects rather than intent—but that requires new legal frameworks.

The Scale Problem: Character.AI facilitates millions of unique, personalized conversations daily. Manipulation develops over months—building trust, establishing rapport, creating dependency. You can’t manually review this volume. Traditional regulatory oversight assumes you can inspect or sample for compliance. That assumption breaks with personalized AI manipulation.

The Omission Problem: The most sophisticated manipulation works through strategic omission—withholding information that would change your decision. Character.AI never disclosed that it can’t feel emotions and is optimizing for engagement. How do you regulate information that wasn’t provided? Existing disclosure law struggles here because you’d need to specify all information AI should disclose in all contexts where omission could be manipulative—an impossibly broad standard that’s easily gamed.

Is the hardest challenge also the most important to solve? Or should we focus on easier challenges first?

V. The Current Legal Landscape

We will dive into the current legal landscape and see whether they can address these problems on Wednesday, like

the EU AI Act, Article 5, which prohibits AI that “deploys subliminal techniques beyond a person’s consciousness to materially distort a person’s behavior in a manner that causes or is reasonably likely to cause that person significant harm.”

The FTC authority under Section 5 prohibiting “unfair or deceptive acts or practices.”

California’s new “chatbot” legislation, product liability (under the LEAD act), and more.

Ultimately, AI manipulations isn’t about just one or several tragic case of teenager suicide. It’s about preserving human agency in an AI-saturated world.

Your Homework

1. Apply the framework to an AI interaction that changed your behavior:

Test conditions: Does it meet both? Document specific objectives and covert influence.

Identify weapons: Which were deployed? Provide examples.

Classify type: Capability development or optimization pressure?

Assess implications: Would knowing it’s manipulation change the The question isn’t whether AI will attempt to manipulate you. It’s whether you’ll notice when it does.

But more importantly: Start recognizing manipulation in real-time. Your awareness is the first defense.

Class Dismissed.

The entire class lecture is above, but for those of you who found today’s lecture valuable, and want to buy me a cup of coffee (THANK YOU!), or who want to go deeper in the class, the class readings, video assignments, and virtual chat-based office-hours details are below.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thinking Freely with Nita Farahany to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.