When Invisible Algorithms Judge You (Inside my AI Law and Policy Class #19)

Civil Rights, Equity, and Human Rights

8:55 a.m., Wednesday. Welcome back to Professor Farahany’s AI Law & Policy Class. (Hi from Paris, where I’ve just arrived to attend a meeting at the OECD. And where I watched Mission:Impossible, The Final Reckoning on the plane. So now I can’t stop thinking about the “Entity” as being the AI we’re talking about today).

Envision this. Arshon Harper, sitting in Detroit, stares at his screen. He has just submitted another IT application to Sirius XM Radio. Minutes later, he gets a message back (not quite from the “Entity” but basically) stating: “Unfortunately, we have decided to move forward with other candidates.”

Same company. Different position. This is his 150th attempt at a job there over two years. He’s more than qualified for most of the jobs he’s applied for, with more than a decade of IT experience. But something is systematically blocking him, and he has no idea what it is.

I want you to pause here and pull up a browser on your phone or your computer. (I promise, this will make sense in a minute and we’ll come back to Harper).

Now, I want you to search for a flight from your city to New York, next Friday returning Sunday. Don’t book it! (Well, unless you really want to). I just want you to notice the first price that you see.

In my live class with your Duke Law counterparts, all the students searched at the same time for flights from RDU to NYC next Friday to Sunday. The result? We ended up with a wide range of prices ranging from $27 to $326.

To make sure we were comparing apples to apples, we then all pulled up Delta Airlines, and searched for the same thing, RDU to NYC next Friday to Sunday. Our results clustered more closely, but varied from $247, to $297, to $257.

Same flights. Same time. Searching from the same classroom. With different prices.

Why? An algorithm (happily not the Entity just yet) judged you (and them) based on device type, browsing history, location, search patterns, and inferred income. Not sure how this works? Go back and check out Class #18, Data Privacy in an AI World. AI decided in milliseconds what you would be willing to pay.

Before this exercise, some of the students in the live class were aware pricing varied over time for flights, but they thought this had something to do with supply and demand for flights.

So we tried again … this time for a pink cashmere sweater. Wildy varying prices across the room. Now you see how much we are all subject to algorithmic price differentiation without even realizing it’s happening.

Hold that answer. Now imagine the same invisible differentiation determining employment, housing, credit. That’s what Harper alleges happened to him in his lawsuit against Sirius XM and iCIMS. Whether he’s right—and whether that’s necessarily wrong—is more complicated than it appears.

Consider this your official seat in my class—except you get to keep your job and skip the debt. Every Monday and Wednesday, you asynchronously attend my AI Law & Policy class alongside my Duke Law students. They’re taking notes. You should be, too. And remember that live class is 85 minutes long. Take your time working through this material.

Why This Class Now. The Convergence Point

“Professor Farahany, we covered AI bias in Class 9. Why are we back here?”

Because every class this semester has in some way been about equity—whether we acknowledged it or not. So, we’re taking it on squarely to see how it shapes AI policy. And we are at a convergence point in the semester, where we are going to start to see the frameworks informing different approaches to AI governance taken by the US, EU, and China. Looking back at some of our past classes this semester:

Class 1’s AI definitions? They determine which legal frameworks apply. Define AI as “advanced statistics” versus “automated decision-making affecting fundamental rights” and you’ve chosen a regulatory regime.

Class 5’s $1.5B training data settlement? If training data reflects historical discrimination, should AI reproduce those patterns (proven predictors) or diverge from them (justice over accuracy)?

Class 7’s DeepSeek breakthrough? Who has access to compute determines who builds AI systems—and whose communities benefit.

Class 10’s transparency crisis? Anthropic can map only 1% of Claude’s features. The other 99% remains unknowable. How do you prove discrimination when the decision-maker can’t explain its own reasoning?

Every technical choice, from compute, training data, transparency, to control, has also been a choice about equity. And every legal framework we’ve studied, from copyright, to transparency laws, export controls, and civil rights, hasn’t yet prevented the harms we know are here and are coming.

And you? You just experienced algorithmic discrimination in real-time during this class.

Three Frameworks, One Crime Scene

Harper ended up with one hundred fifty rejections from one company using one AI tool, the iCIMS Applicant Tracking System, over a two-year period. He filed a complaint against the company and iCIMs on August 4, 2025, in the Eastern District of Michigan, alleging Title VII and Section 1981 violations, and seeking class action status.

But who’s responsible? The employer who deployed it? The vendor who built it? The historical bias in the training data? The legal frameworks that can’t stop it?

We’ll examine this through three frameworks embodying fundamentally different philosophical commitments:

The Prosecutor (U.S. Civil Rights Law): Can we convict anyone? Reactive, individual remedy, preserve innovation until harm is proven.

The Forensic Expert (Equity-Centered Design): Could harm have been prevented? Proactive, center affected communities, accept slower innovation.

The International Inspector (Human Rights Norms): What should universal standards require? Proactive duties, dignity over efficiency.

Each will reveal something the others miss. None can solve the case alone. That’s not a flaw—it’s the fundamental challenge of AI governance.

1. The Prosecutor (Civil Rights Framework)

Harper can sue under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and 42 U.S. Code Section 1981. He has some recent precedents on his side, too, to sue not just Sirius XM, but also iCIMS (the third-party vendor of the AI software) that Sirius XM used for hiring. Like:

Louis v. SafeRent Solutions (D. Mass.): Mary Louis and Monica Douglas filed a class action lawsuit in 2022 claiming that SafeRent violated fair housing and consumer protection laws by using its SafeRent Score product to make rental housing decisions for applicants in Massachusetts holding public housing vouchers. The court denied dismissal July 2023, and a settlement was approved November 20, 2024 for $2.275 million plus injunctive relief. Critically, the U.S. Department of Justice’s January 2023 Statement of Interest argued that the Fair Housing Act reaches tenant screening vendors, not just landlords, because SafeRent “effectively controls the decision to approve or reject a rental application.”

Mobley v. Workday (N.D. Cal.): Derek Mobley applied to 100+ jobs through Workday’s platform, and was rejected every time. (Go back to class # for a deeper dive on this). In May 2025, the court certified preliminary collective action for age discrimination. Judge Rita Lin’s July 2024 ruled provisionally that when software makes actual decisions (screening, ranking, rejecting), the vendor can be an “agent” of the employer under Title VII.

California FEHA Regulations (effective October 1, 2025): Codified vendor liability in California, making clear that the regulations explicitly extend liability to an employer’s “agent,” anyone “acting on behalf of an employer... including when such activities and decisions are conducted in whole or in part through the use of an automated decision system.”

The Joint Statement from CFPB, DOJ Civil Rights Division, EEOC, and FTC identified three sources of AI discrimination: “data and datasets” reflecting historical bias, “model opacity” making anti-bias diligence impossible, and “design and use, “from deploying tools in untested contexts.

But even with this federal recognition, Harper need data on all Sirius XM applicants (demographics, outcomes), statistical analysis showing disparate impact, expert witnesses at $500/hour, employment discrimination lawyers, discovery specialists to fight trade secret claims. He’s looking at a minimum of 3-5 years of litigation.

Meanwhile, Sirius XM continues using iCIMS. The system continues screening thousands of applicants. Hundreds or thousands of other qualified Black applicants may be subject to discrimination.

Let’s Consider Two Opposing Perspectives on The Civil Rights Approach:

In favor of reactive enforcement: It preserves innovation (no restrictions until actual harm is demonstrated). And it puts the burden of proof on the accuser to prove a violations has actually occurred. This is good for market efficiency, in that algorithms can optimize systems without putting preemptive limits on them. Which means that we achieve proportionate remedies, where only violators face liability. (After all, maybe the algorithm rejected Harper for legitimate reasons. Maybe his qualifications didn’t match the specific needs of the company. Maybe stronger candidates existed.) Requiring proof of wrongdoing would protect companies from false accusations.

In opposition to reactive enforcement: This remedy operates only after extensive harm may have already occurred (for Harper, that’s 150 rejections). And it’s an asymmetric burden, where the person harmed (Harper) bears all the upfront costs of challenging the system. And any remedy to the system moves slowly while the system (if discriminatory) continues. Plus, it only provides an individual remedy without actually fixing a potentially broken system, thereby disadvantaging those who can’t afford litigation. If an algorithm is systematically discriminating, waiting 3-5 years means thousands of additional victims. The framework assumes individuals can bear the burden of fixing systemic problems.

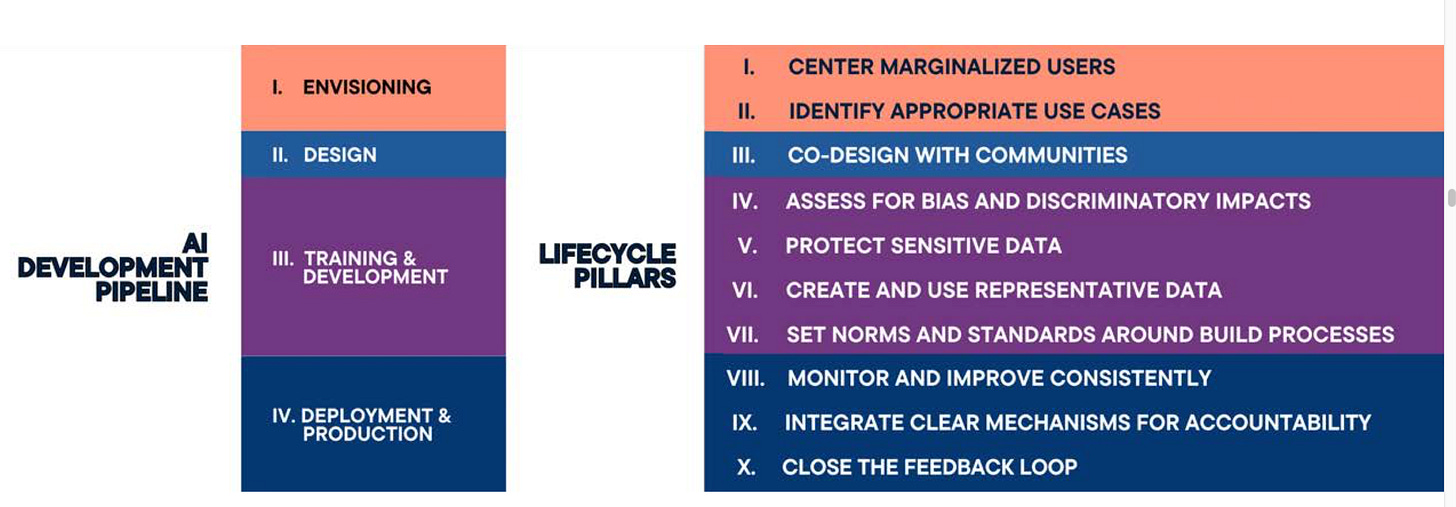

In fairness, some argue that a civil rights framework, could operate proactively in the entire AI life cycle. This framework, from The Center for Civil Rights and Technology (a joint project of The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights and The Leadership Conference Education Fund), in their report, The Innovation Framework: A Civil Rights Approach to AI, envisions such a centering.

But as Harvard Professors Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev convincingly show in their article, The Civil Rights Revolution at Work: What Went Wrong, “When victims of discrimination sue, the legal system rarely protects them from retaliation and rarely rights employers’ wrongs.”

The Verdict?: Civil rights law provides a path to remedy for AI harms—but only for those who can afford the journey. Whether that’s the right trade-off depends on your values toward innovation versus prevention, individual rights versus collective protection, and market efficiency versus proactive justice.

2. The Forensic Expert (Equity Framework)

The equity framework focuses on how was this system designed? Could different choices have prevented harm to people like Harper?

Penn State Dickinson Law Professor Daryl Lim in his article, Determinants of Socially Responsible AI Governance, argues that “equity, and the rule of law” should serve as “yardsticks of socially responsible AI,” and uses that framing to compare US, EU, China, and Singapore AI governance.

The World Economic Forum focuses its equity framework on organizations, rather than laws, to achieve “equitable and inclusive artificial intelligence outcomes” in their 2022 report, A Blueprint for Equity and Inclusion in Artificial Intelligence.

How would the choices that iCIMS made differ if it had designed its system through the Lim or World Economic Forum equity lens?

It likely would have meant testing their system on diverse populations, auditing it for proxy discrimination, building in an appeal mechanisms, providing explanations for the scores it generated, consulting stakeholders, implementing human review for borderline cases, creating a correction processes, and publishing validation studies by demographic group.

While the U.S. does not mandate an equitable design process, laws like N.Y. Local Law 144 (which we discussed in Class #9), and California’s October 2025 regulations are moving toward requiring bias testing, but these are outliers, so far. And our discussion of N.Y. Local Law 144 in Class #9 made clear, this isn’t working particularly well.

The equity frameworks can be boiled down to asking four important questions:

Whose experience mattered during development? Was the system tested on diverse populations? Were there public bias audits before it was deployed? Is there a built-in appeal process? Did iCIMS consult with Black IT professionals and other relevant stakeholders? By asking these questions we can see whether the system is optimized for legitimate business goals like optimizing efficiency, processing applications quickly, reducing time-to-hire, and minimizing human involvement. And whether the communities most likely to be benefited or harmed (by something like proxy discrimination) were considered during the design process.

Who bears the burden when the system gets it wrong? In the case of someone facing discrimination, likely the person harmed. Harper undoubtedly put many hours and weeks of work to submit his 150 applications. Both the process of applying and the repeated rejections from jobs had a psychological toll. During that time, he suffered lost wages and stagnation in his career. For Sirius XM/iCIMS? They bear zero costs until they are sued, suffering no damages or restrictions while purportedly deploying a discriminatory system. By asking this question we can surface asymmetries in burdens when things go wrong and take corrective actions to address it.

What fallback mechanisms exist in the automated system? When Harper was rejected for the 50th, 100th, 149th time, could he appeal the decisions, receive an explanation beyond the generic rejection letter, ask for a human review, or see his score? An “equity” framework would call for these features. Instead, Harper was judged by an invisible system using invisible criteria, producing unchallengeable decisions.

This is “procedural inequity,” where even if the algorithm were substantively fair, the process itself denies dignity and agency.

But should every automated rejection require human review? Would that eliminate efficiency gains making screening valuable?

Does the system perpetuate or disrupt historical patterns? iCIMS’s algorithm presumably learned from historical hiring data reflecting decades of discrimination. Rather than disrupting bias, it may have entrenched it, by making discrimination faster, more consistent, harder to detect, and easier to deny responsibility for. Sirius XM can now say: “The AI decided, not us.”

But historical data also reflects what worked, such as who succeeded in roles. If certain patterns predict success, is using them discriminatory? Or rational? Should companies deliberately diverge from proven patterns? Is “less qualified according to history” the same as “less qualified in reality”?

The Verdict

Harm to Harper may have been preventable through equity-centered design. But do legal requirement to design equitably strike the right balance between competing values in AI development? What would it require? Pre-deployment safety testing and approval like for drugs and medical devices? Demanding stakeholder consultation? Building appeals into every high-stakes AI system?

The equity framework prioritizes prevention and collective protection over efficiency and speed. Is that the right balance of interests?

3. The International Inspector (Human Rights Framework)

The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, adopted by 193 member states, establish that businesses should commit to respecting human rights through policy, conduct human rights due diligence before deploying systems that affect people’s lives, provide remediation when harm occurs, and maintain transparency about how systems work.

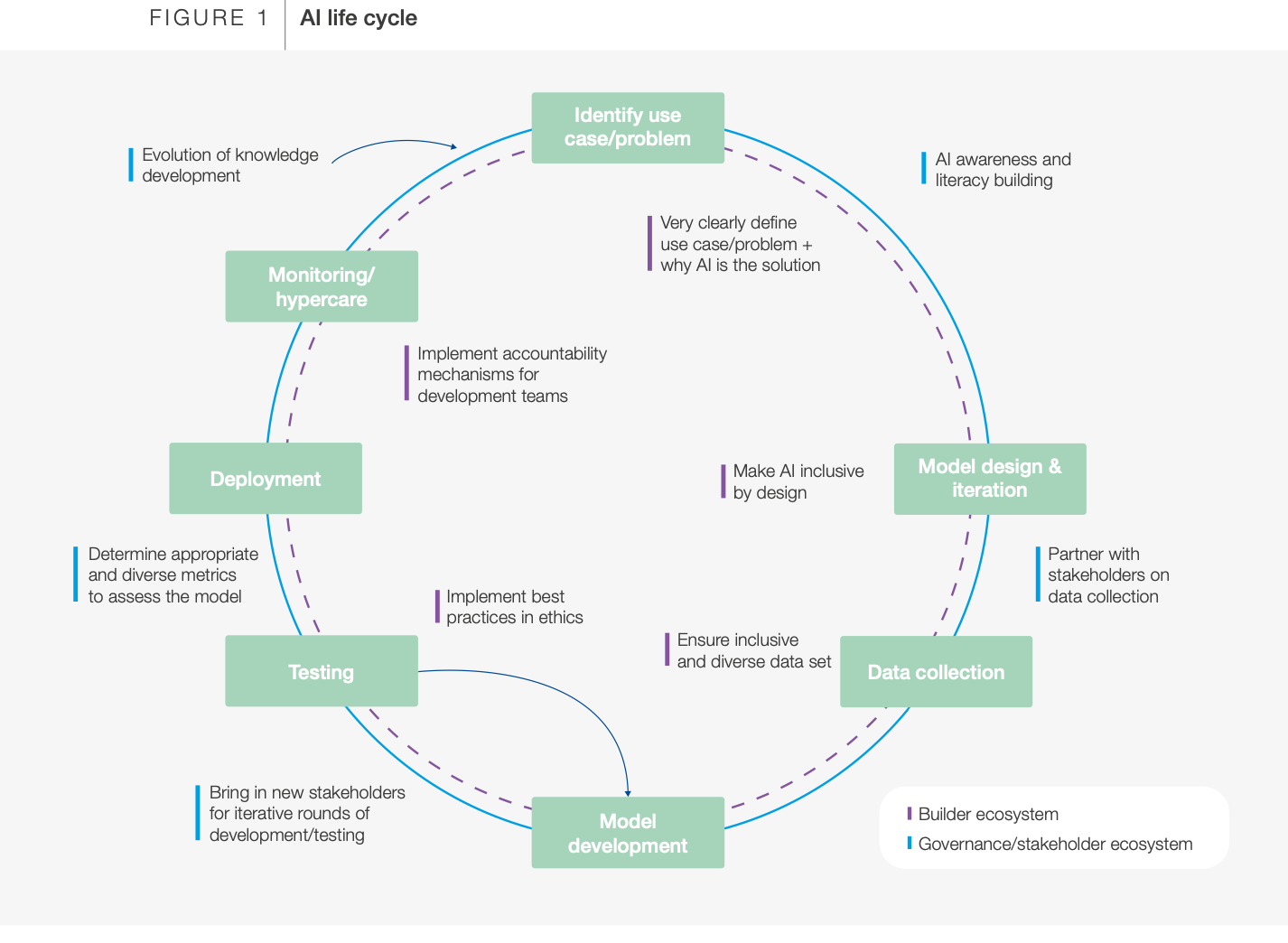

The U.S. State Department’s July 2024 Risk Management Profile for AI and Human Rights explicitly maps these obligations to the NIST AI Risk Management Framework, creating a bridge between human rights due diligence and technical risk management.

In March 2024, all 193 UN member states adopted a resolution calling for human rights to be respected throughout the AI lifecycle—from design through deployment through decommissioning. The whole world knows algorithmic discrimination violates fundamental rights. So why are people like Harper still facing alleged algorithmic discrimination in hiring?

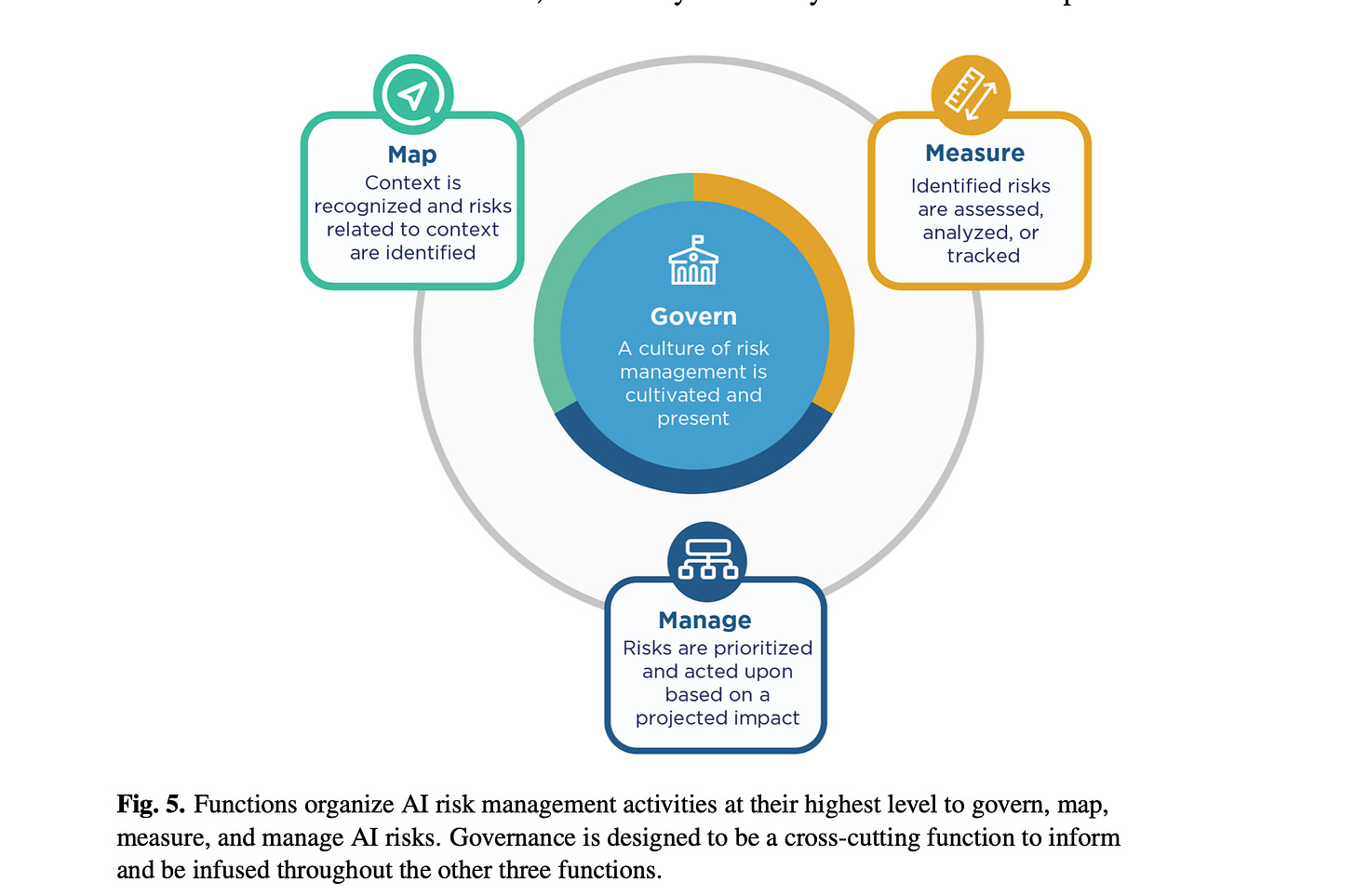

The NIST AI Risk Management Framework has four core functions where organizations should proactively assess human rights impacts. Let’s test how these might have applied to Harper’s situation.

Under “Govern,” (“Policies, processes, procedures, and practices across the organization related to the mapping, measuring, and managing of AI risks are in place, transparent, and implemented effectively”), we’d want to know whether Sirius XM or iCIMS have policies on respecting human rights in AI deployment? Or:

Is there Board-level accountability for AI risks?

Clear lines of responsibility when AI systems discriminate?

Public evidence of governance-level human rights analysis before deploying a tool that makes life-altering decisions for thousands of applicants?

The NIST framework recommends this as foundational to the entire framework, in that you can’t manage risks you haven’t acknowledged at the governance level.

The Map “function establishes the context to frame risks related to an AI system.” This NIST AI RMF Playbook lays out for each of these functions suggested actions, which we can use to ask:

Did iCIMS identify risks to the right to work (Universal Declaration of Human Rights Article 23) during design?

Did they consider the positive and negative impact to individuals, groups and communities (such as to Black IT professionals), including whether certain data points might serve as proxies for race?

Under “Measure,” an organization would develop “approaches and metrics for measurement of AI risks enumerated during the Map function,” “starting with the most significant AI risks.” Here, we’d ask questions like:

Did iCIMS test for disparate impact before selling the system to Sirius XM?

Did they determine appropriate performance metrics, such as accuracy, of how their AI system would be monitored after deployment?

Did they take corrective actions to enhance the quality, accuracy, reliability, and representativeness of the data?

Under “Manage,” organizations would allocate risk resources to mapped and measured risks on a regular basis. Now, we might want to know:

When Harper was rejected 149 times over two years, was there any process to investigate whether something was systematically wrong?

Were there response and recovery, and communication plans for the identified and measured AI risks?

Were these documented publicly to prevent additional harm to other impacted users?

The Rights at Stake

Harper’s situation implicates multiple fundamental human rights. His right to work under Article 23 of the Universal Declaration. His right to equal protection under Article 7 (if he faces systematic discrimination in employment access). His right to effective remedy under Article 8, including whether he has a meaningful mechanism to challenge algorithmic decisions before resorting to expensive litigation. A human rights lens would be concerned with whether he ever consulted about systems judging him, informed about how decisions were made, and given a voice in design choices affecting his livelihood.

The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights requires several core elements: policy commitments to respect human rights (neither Sirius XM nor iCIMS appears to have published such commitments regarding their AI tools), human rights due diligence process before deployment to prevent, mitigate, and account for how they address their impacts on human rights (no public evidence that this occurred for iCIMS’s system), processes to enable remediation when harm occurs (only after being sued, not proactively).

The 2025 Freedom Online Coalition statement declared that private actors should take “meaningful responsibility for respecting human rights” including by incorporating “safety-by-design and governance models in order to identify, mitigate, and prevent adverse human-rights impacts linked to their activities.”

Did that happen with Sirius XM and iCIMS? Should it have?

Two Competing Perspectives

Consider the argument in favor of this human rights framework: It establishes universal baselines that apply to everyone everywhere, not just protected classes in specific domains covered by national laws. It requires proactive prevention before deployment rather than reactive remedy after harm. It centers affected communities through mandatory consultation, giving voice to those most likely to be impacted. It provides moral authority that transcends national borders and creates reputational pressure even without direct enforcement. And it treats fundamental rights as non-negotiable rather than subject to cost-benefit balancing.

But consider the competing perspective. These are aspirational guidelines, not binding law. Harper can’t sue under the UNGPs or compel due diligence. There’s no enforcement mechanism, no penalty for non-compliance, no remedy when organizations ignore these standards. The framework assumes organizations will voluntarily comply out of moral commitment or reputational concern, but market incentives often pull in the opposite direction.

Moreover, if Sirius XM had conducted “human rights due diligence” and “stakeholder consultation” before deploying iCIMS, would it actually have prevented Harper’s rejections? Or would it have generated expensive paperwork that didn’t change underlying outcomes? Would adding international human rights requirements make AI development prohibitively expensive, particularly for smaller companies? Would it give larger, well-resourced companies even more competitive advantages?

The Verdict

The International Inspector discovered that international consensus exists, proactive duties are clearly defined, and universal norms apply to everyone. But these norms lack domestic enforcement mechanisms. What would it take for human rights frameworks to actually work? Make them enforceable. Create private rights of action so individuals like Harper can sue for violations. Establish fast-track administrative procedures that don’t require years of litigation. Give international norms domestic legal force through implementing legislation.

The human rights framework prioritizes universal dignity and participation over efficiency and national sovereignty. Whether that’s the right trade-off depends on your values. Do you believe fundamental rights should constrain all AI development regardless of innovation costs? Or do you believe aspirational international standards without enforcement are effectively meaningless?

The Three Detectives Report

The Prosecutor found enforcement, right to sue, potential damages—but it’s reactive (only after 150 rejections), slow (3-5 years), expensive (experts Harper can’t afford), and provides an individual remedy without structural or systemic change.

The Forensic Expert showed prevention was possible, identified design failures, demonstrated equity approaches could have stopped harm, but it’s not legally enforceable, there is no penalty for ignoring the framework, and you can’t sue for “failing to design your AI system equitably.”

The International Inspector revealed proactive duties, universal scope, required participation, and moral authority, but there’s no enforcement mechanism, it’s not binding in US courts, and organizations can and often do ignore their human rights obligations without consequence.

Would the ideal system combine all three?

The Comparative Governance Question: Why Different Countries Made Different Choices

As we approach the end of the semester, we’ll be building on these frameworks as we look at country-level policy decisions in how they govern AI. Such as:

The United States: Reactive Individual Remedy

Thus far, the U.S. seems to be in a “wait and see” approach of reacting to harm, providing individual remedies when they arise, and fostering innovation. The logic is straightforward, that free markets drive innovation, so we ought not restrict algorithmic tools without proof of harm.

This approach tolerates Harper’s suffering—individual plaintiffs grinding through years of litigation while harmful systems continue operating—because we prioritize innovation and market efficiency. And treat the potential benefits of rapid AI development, efficiency gains, and reduced costs as justifying individual casualties who can theoretically seek remedy.

The European Union: Proactive Prevention

We do a deep dive next week into the European approach to AI governance, where Europe has taken a more proactive approach to harm, trying to prevent it before deployment, while accepting slower innovation as a result. Their logic reflects entirely different priorities: fundamental rights require protection before violation, not just remedy afterward. Collective welfare matters more than individual efficiency gains. Companies should prove safety before deployment, not after causing harm. Universal human rights apply to everyone, not just protected classes in specific domains.

The EU AI Act, which we’ll study in more detail few weeks, operationalizes these values through mandatory risk assessments (Articles 9-10), requirements for high-risk AI systems (Articles 8-15), human oversight provisions (Article 14), and transparency obligations (Article 13). Companies deploying high-risk AI must conduct conformity assessments, register systems with authorities, and maintain technical documentation proving compliance.

This approach tolerates slower innovation, regulatory burden, and market friction because Europeans prioritize prevention and collective rights. They believe preventing harm to vulnerable populations justifies accepting innovation delays and compliance costs.

But this approach also prevents deployment of systems that might harm some people even if they benefit many others. It potentially disadvantages European companies in global markets where competitors aren’t bound by similar requirements.

China: State Control

China chose top-down government determination of acceptable uses. Their logic reflects fundamentally different assumptions about governance: social stability and collective harmony trump individual rights claims. State expertise, not market forces or individual lawsuits, determines appropriate technology deployment. There’s no independent enforcement—government decides what’s permissible. National interests override commercial interests.

China’s approach, which we’ll examine when we study comparative AI governance, seems to prioritize social stability and state control above individual rights or market efficiency. Which may align AI development with national strategic goals rather than market incentives.

The Point is Not to Decide Which of These is “Better”—They Reflect Different Values About What Matters Most

This is the hardest thing for students to accept, but it’s intellectually essential: there is no objectively correct framework. Each reflects different beliefs about the role of law (reactive versus proactive), the nature of rights (individual versus collective), the balance between innovation and protection (which should yield when they conflict), and whether prevention or remedy should be prioritized.

The question isn’t which approach is “right.” It’s what are you willing to sacrifice to get the governance regime you prefer?

I’m not asking you to solve this. Instead, I’m asking you to be intellectually honest about what you’re willing to sacrifice.

Closing: The Algorithm Is Still Running

We opened with dynamic pricing. With dynamic pricing by individual. Some of you think that’s efficient. Others think it’s discrimination. Your answer reveals your values.

Then I showed you similar differentiation in employment (and the same is happening in housing, credit, insurance, and more). But in most of these cases, you can’t comparison shop. You just get rejected without explanation.

Harper’s case helps us see that if algorithms trained on historical data inevitably reproduce discrimination—at scale, at speed, and invisibly—can any legal framework actually stop it? Or are we just choosing which communities to sacrifice for the benefits of the technology? We can also see:

From civil rights law: Liability must attach to not just the employer/company but the vendor, as well. SafeRent, Mobley, California FEHA all establish that AI vendors can’t hide.

From equity principles: Design matters. Prevention through consultation, testing, appeals could stop harm before it occurs. But what’s the incentive for companies to integrate these principles?

From human rights norms: 193 countries agree rights should align AI development with human rights. But through what enforcement mechanism and what will drive that alignment?

At least one thing is certain (this scene echoes in my mind after watching Boss Baby this weekend with my kids. If you know, you know):

Every time you search for a flight, an algorithm judges you.

Every time you apply for a job, an algorithm evaluates you.

Every time you seek housing or credit, an algorithm assesses you.

The question is whether our legal frameworks will (and whether they should) catch up before millions more people are invisibly rejected for reasons they’ll never understand.

Class dismissed.

The entire class lecture is above, but for those of you who found today’s lecture and this work valuable, who want to buy me a croissant or canelé in Paris today (THANK YOU!), or who want to go deeper in the class, the class readings, video assignments, and virtual chat-based office-hours details are below.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thinking Freely with Nita Farahany to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.